(No reproduction of this material can be used without permission)

of the Monovisions Magazine Website

There will be four posts (Part 1, 2, 3, & 4) for this group of diaries that I have belonging to Alexander Watson Dunlop. On our podcast, Diary Discoveries, we devoted 4 episodes to this man’s life. After we released them I received several requests saying they’d love to read the full transcript from his diaries, so what better place to put those complete transcripts, then here. You can also see even more photos from this group on our Diary Discoveries web site on the links I’ve provided below.

Alexander Watson Dunlop born in 1862, was a Scottish Doctor and ships surgeon who attended Glasgow University where he received his medical degree. But before all of his schooling begins, Alexander writes a marvelous “coming of age” story that took place when he was just 11 years old and he calls it “The Fenwick Escapade.” Enjoy reading, real stories, about real people, in their words….

The very first page of Alexander Watson Dunlop’s Diary, written in 1881.

“INTRODUCTION: For a longtime I have been considering that a short, sketchy history of my doings written at this time would be very interesting to me as a man of fifty, if I am destined to live to that age. This idea has taken such forcible hold on me that I am determined to commence forthwith. I do not, however, intend to bother myself much about composition, it is too much trouble but simply to write down things as they occur to me, and when having written my past doings, I shall have come to the present day, to simply transcribe what actions and events shall seem to me to be noteworthy. At present I am 19 ½ years old, 5-9 in height etc. I wish merely to record the age at which I began to write for I will now turn back considerably. History or lives generally begin with the birth and as my birth was just as important to me as any other man’s to him I shall commence with that.”

I was born then on the 5th of March, 1862. I cannot exactly say at what hour. It was probably during the night as most births are, because then the doctor doesn’t care much about the bulge in his coat pocket caused by the box containing the baby. Nor can I say whether the night was bright or very dark, whether it was wet or dry, tranquil or stormy. I have no distinct recollection of these things being so young. I have only been able to make some inferences. 1st. That it must have been quite an ordinary night as regards to light, because I am of that disposition which at one time looks at the bright side of things and at another time takes a gloomy view of life. 2nd. That it must have been a dry night for since coming to years of maturity, I find that I know a good glass of beer when I drink it, and hardly ever refuse liquor when it is offered to me. 3rd. That the night must have been a little gusty because though generally good-natured I am inclined when in the slightest degree bothered to shew temper.

So much then for my birth. I will now pass over several years of my early childhood and commence the history of events by an episode which I think will never be forgotten by me even without the aid of this history.”

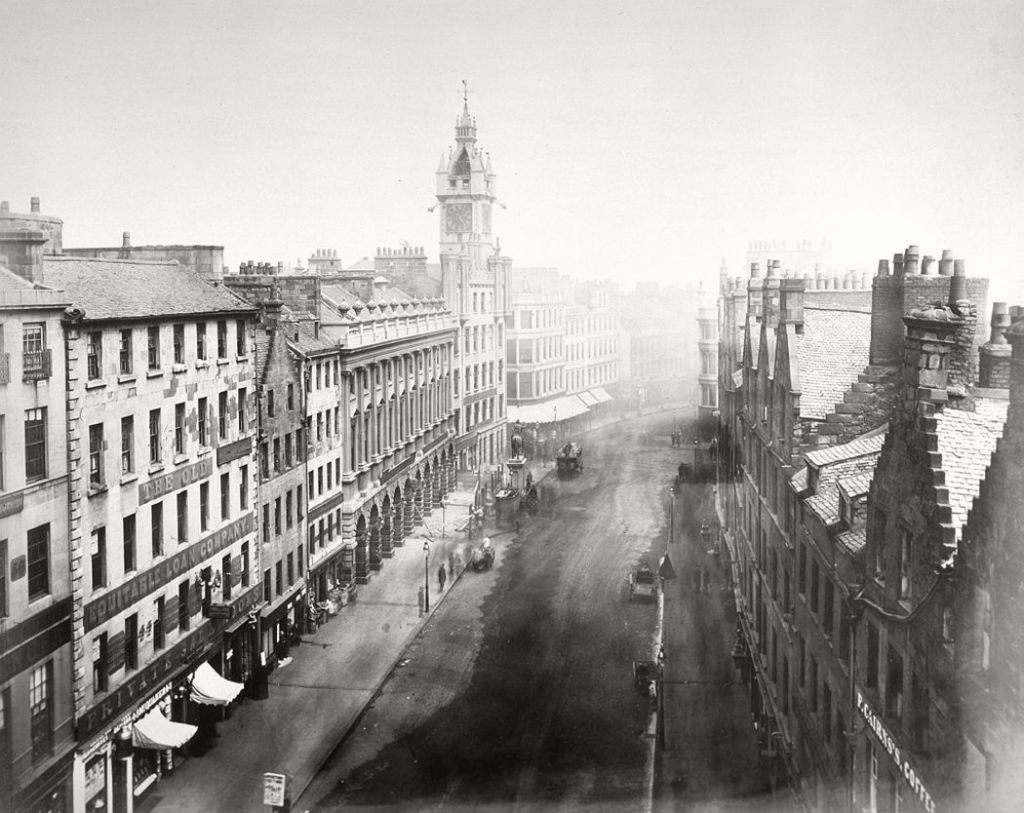

Two more scenes of Glasgow during the time Alexander was beginning his diary.

FENWICK (by jabbers)

“When about 11 years of age, I had a strong desire to go to sea. I was of that melancholic disposition which is apt on very small ground to believe itself wronged. I have ever been extremely sensitive. There was another boy in school named Stevenson who was also possessed with a strong desire to go to sea. We became great friends, began to save all our pennies and every night on pretense of learning our lessons retired to a room by ourselves. A map was produced with full rigged ships and ships under full sail. We learned the names of all the sails, ropes and spars, the different kinds of vessels etc. We had also a small globe which we studied. This learning along with the possession of a sheath knife were what we considered the preliminary requisites of a sailor. To procure our knives we must have money and this we saved and also made. One of our plans was this. We made a little theatre about a foot square and bought a series of pictures illustrative of John Gilpin’s career. We fixed these on two small rollers as that they might be turned round in the same way as I have seen it done in front of a barrel organ, each picture coming in succession into the open space in front. Steevie turned the pictures while I recited aloud the verses in explanation. We charged a penny for admission. Of course all my family came little knowing for what purpose their money was intended. In this way by scrupulous saving we made as much as bought two sheathes for knives. I had already got an instrument – a large spring backed knife with a blade about five inches long.

I had a large unfurnished room to work or play in. A little way up the chimney of this room we chiseled a hole into which we put all our treasures. We had amassed about 9 ½ pounds, our time was drawing near. When we thought we would start off we told one or two of our school fellows that we would walk down to Greenock and try to get a ship.“

“We had a better plan however well knowing that if we adopted this one we would be caught. On Friday afternoon Steevie and I were consulting in the lobby of the school and I was just giving him a sheath when the master came out. He saw us, took the sheath and asked us about it. We would tell him nothing. He said he would ask us for an explanation on Monday. On our way home we determined he would not see us on Monday and I unfolded to Steevie my plan which was to walk to Ayr and get a ship there. No one would ever think of looking for us at that place. Steevie was to come for me next morning at 9 o’clock. That night we had a party in the house, a party long remembered by the people who were at it on account of the after circumstances. At 9 o’clock next morning, the Saturday before the April communion 1873, we set out with some little food in our pockets. At that early age I smoked, so did Steevie; we purchased a supply of black twist. We took the road straight out Eglinton St. through Mearns. I remember we were very jovial, smoking all the way. It was a good day and we walked steadily on. It was getting dark when we reached Fenwick 17 miles from Glasgow and four from Kilmarnock.“

About ½ a mile before we entered Fenwick we had passed a very dense fir wood which we thought would be the very place to pass the night in. We purchased a large loaf and some cheese in the town and retraced our steps. We entered the wood, penetrated into the heart of it and selected a suitable spot. We gathered together small branches and twigs for a bed and then sat down to eat something. When we had satisfied ourselves I rolled up the loaf making a pillow of it. By this time it was quite dark, we heard rain pattering on the outside branches. Two men with guns passed away to our right. They fired them off. This stirred up some crows and owlets. They began to cry in a most dismal fashion. Altogether we were not comfortable. Steevie at length got up and said he was not going to stay here. I was not in the least averse to going away. We found our way to the edge of the Plantation, clamored over the fence and were in the road again. It was raining very heavily and we had no topcoats. We got thoroughly soaked before we got to the village. By the aid of matches we examined a shed or two but could not find anything to suit us. Finally we went to the Inn. I remember the scene and conversation well. The house was approached by a pair of flights of steps coming from either side and meeting on a platform before the door. A girl answered our summons. I asked her if we could have a bed for that night. We had come from Glasgow intending to walk to Kilmarnock but could not go any further. I said we had no money but that it would be sent to her from Glasgow. She answered that all the beds were being cleaned and aired just now, that they hadn’t a single one ready and that she could not take us in. We turned sorrowfully away and went to the woman from whom we had bought the provisions. She directed us to go on another half mile until we came to Upper Fenwick and there we would find a lodging house. We trudged on through the rain and by and bye found out the house. We told the woman the same story as had been given at the Inn. She was a kind person and seemed to guess the truth. She invited us in and glad we were to sit down before the huge kitchen fire. Our clothes were allowed to get dry upon us. This accounts for the story afterwards made out that we had kindled a fire in the wood, because there was a smell of burnt cloth about our clothes ever afterwards.

Round the bright fire were three or four men. In the big chaise sat Mr. Jamieson, the master of the house. On his right sat a man well known throughout the country. Everyone knew Barnie Peerie, the Sweep; he was a celebrity. I do not remember the other two meant who sat on my right. Steevie and I sat in the middle side by side. Barney was talking about himself; he said he had been born at Demerera (?). Then the talk turned round to a story about a fish which had been got up one of the drains opening into the Clyde. It was Barney who told the story. He appealed to me as coming from Glasgow. Steevie was sitting in fear and trembling and when I spoke he nudged me and looked at me gravely and reproachfully as much as to say, “Why can’t you keep quiet; we’ll both be murdered. By and bye the men retired across the passage into the lodging part of the house. Mrs. Jamieson told us we could sleep in the kitchen with her boy. She spoke to us in a kind way different from the tone which the husband used when addressing us. We got into bed and slept soundly. The story which my father tells, that I slept with Barnie Peerie is untrue. I did not even sleep in the lodging house. I was never in a cleaner bed or with cleaner company. In the morning when I awoke I found the woman at the bed side gazing at us. She had a sad pitying expression on her face. I could not look at her but turned away my head. We got up and dressed and had breakfast scarcely speaking. Mrs. Jamieson counseled us to go home saying many things to urge this course upon us. We did not need much persuasion to determine us. In fact without saying anything we seemed eventually to agree that we would go home. Steevie’s cravat was taken as a pledge of payment. I shall not soon forget Mrs. Jamieson; she was a good woman. Some time afterwards Father and mother when staying in Kilmarnock drove over to see her, but found that she was dead.

By 10 o’clock we had started off on our homeward journey. Meanwhile at home they had been in a great state. No one had gone to bed. Our school fellows were questioned and told what they knew. Telegrams were dispatched to Greenock to search the town and the ships. Each of my brothers was sent a different way to look for me. One went to Duntocher a village more than half way to Dumbarton to see some friends there. No one went to church and it being Communion Sabbath, many inquiries were made the consequence being that everyone who knew me knew that I was off. Great surprise was expressed as I had always been very quiet and innocent looking. Many thought it was my elder brother Willie.

Coming across the Broomielaw bridge we met Johnnie. He had been to the station to see if father could get a train to Greenock that night. We all walked home together quite quietly although Johnnie had told us that if we offered to run he would call a policeman. When we came in we found them all assembled in father’s consulting room. Steevie’s sister was there also. I remember well my father’s kind expression as he looked at us. He laughed as he lifted us by the jacket collar on to the hearth rug, then stepped back, looked at us and laughed again. Just after we came in a telegram came from the Greenock police officer saying that they had searched the town and all the ships in the harbour but no boys answering the description were to be found. My father chuckled as he read it, crushed it up and threw it in the fire. We sat silently down on the sofa and here I produced two huge fir tops which I had brought from the wood. For many a day they lay on the mantle piece. I will never forget my father’s kindness to me. He never spoke a word to me in anger about the affair. He treated it as a joke and for many a day he laughed as he told it to all friends who came in. I could not ask him not to speak of it because he so laughed at it. For a long time I was questioned even by the grocer when ordering messages, “Are you the boy who ran away?” I am still sometimes assailed with the name of Fenwick and when bothering anybody am told to go to Fenwick. This is the story of the “Fenwick Escapade.” I never more mentioned sea. We sent money to Mrs. Jamieson and Stevie got his cravat back. I heard afterwards from a friend that Barney Peerie had been put in jail for stealing lead off roofs, which elicited the remark, “Grand company you were in.” Poor Barney he is now dead, Requiescat in peace.”

Well, there you have it for Part I. We have a podcast called, “Diary Discoveries” and if you haven’t already listened to our Podcast devoted to this post, you can here it at the following links.

[…] https://sallysdiariesprivatecollection.com/2025/01/06/dr-dunlops-scotland-pt-1-the-fenwick-escapade-… […]

LikeLike

This is Sally. We got an amazing comment from a listener who wanted me to share here what he wrote us about this particular episode. It’s the comment I made when Dr. Dunlop said, I was born then on the 5th of March, 1862. I cannot exactly say at what hour. It was probably during the night as most births are, because then the doctor doesn’t care much about the bulge in his coat pocket caused by the box containing the baby.“

I remember saying that I wasn’t sure of what me meant by that. Well our wonderful listener found out and it really must be shared, and I quote…..

Sally and Jeff, I’m enjoying the diary of Dunlop. I wanted to leave a comment but wasn’t sure where to leave it….Here’s my answer to a question you raised. What is the meaning of Dunlop’s diary entry describing an 1860’s Scottish doctor traveling at night to attend a birth with a box for the baby in the pocket? I don’t imagine he was describing the modern tradition of providing a gift box of essential items to a Scottish newborn. Perhaps Dunlop’s knowledge was based upon the experiences of his own father, a doctor. My first impression while listening to your podcast was that the box was for use after the birth of a possible stillborn.

A search of the internet generally states that the infant mortality rate in 1860’s Scotland and UK was 150-200 deaths per 1,000 births, or about 15-20 percent. That’s pretty high. In the UK in 1800, one in three children did not make it to their 5th birthday. An article on the University of Glasgow website entitled, “Scottish Way of Birth and Death” states in relevant part that “A stillborn baby’s body could be disposed of without ceremony (in some cases the doctor persuaded parents to let him take it away for research purposes.)”

https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/socialpolitical/research/research-projects/scottishwayofbirthanddeath/death/stillbirths/

So, it is this listener’s best guess that attending Scottish doctors in the 1860s (one-in-five) that the baby would be stillborn, and they had better be prepared to discreetly dispose of the baby’s body, and traveling at night avoided unnecessary looks and the need for explanation, as well as providing some privacy. Could be.”

LikeLike